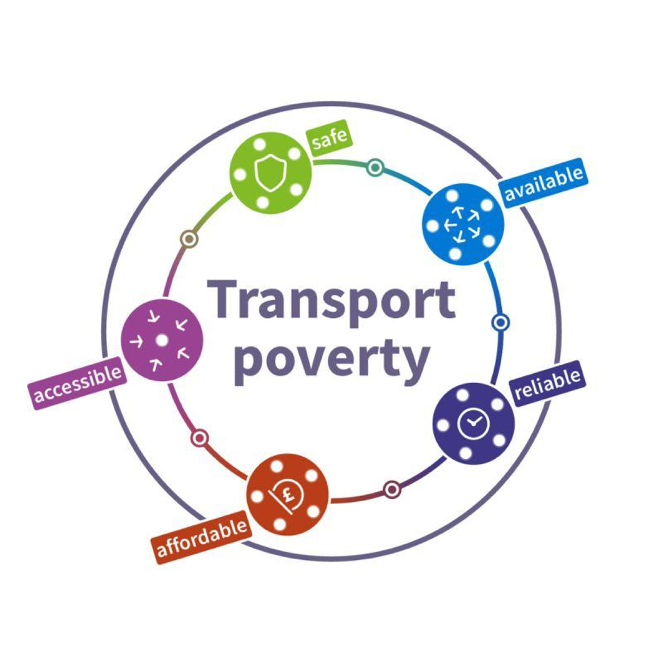

The Key Dimensions framework focuses on two essential aspects: Accessibility and Affordability. These dimensions play a crucial role in ensuring effectiveness and equity in any system or solution.

Accessibility

Accessibility was defined as the “ease with which a person can access services, places or facilities for different interaction possibilities” (Mejía Dorantes & Murauskaite-Bull, 2023, p. 3865).

Accessibility poverty “refers to the inability to reach key social or economic activities in reasonable time, ease and cost” (Social Exclusion Unit, 2003; Abley, 2010; Alonso-Epelde et al., 2023). This dimension replicates the overarching conditions of poverty and is responsible for social exclusion, because modes of transport are necessary to enforce determined rights or fulfil defined necessities (Cebollada, 2006; Alonso-Epelde et al., 2023).

Affordability

Affordability refers to an individual’s ability to pay for transport services without compromising other essential needs, such as housing, food, healthcare, and education. When a significant proportion of income must be allocated to transport, individuals may face financial difficulties that force them to make sacrifices.

For instance, studies by Litman (2021) highlight that transport affordability is central to sustainable transportation planning, emphasizing the importance of considering how costs impact low-income households disproportionately. Similarly, research by Lucas et al. (2016) discusses the links between transport affordability and social inclusion, noting how excessive mobility costs can deepen existing socio-economic disparities.

“Affordability of transport is not only an economic issue but also a question of social justice and accessibility”, as noted by Martens (2017) in his work on transport justice. Addressing affordability often requires integrating equity considerations into public transportation policies or investment in cost-effective transport modes to ensure access for all.

Exposure to transport externalities

Exposure to negative externalities is another dimension of transport poverty. The transport system can lead individuals to excessive negative exposure, as road traffic fatalities or chronic illnesses and deaths due to congestion-associated pollution, (Alonso-Epelde et al., 2023; Barter, 1999; Booth et al., 2000; Planning and Design for Sustainable Urban Mobility.pdf, n.d. as cited in Alonso-Epelde et al., 2023).

List of reference

Abley, S. (2010). Measuring accessibility and providing transport choice. In Australian Institute of Transportation Planning and Management National Conference.

Alonso-Epelde, E., García-Muros, X., González-Eguino, M. (2023). Transport poverty indicators: A new framework based on the household budget survey. Energy Policy, 181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2023.113692.

Barter, P.A., 1999. Transport and urban poverty in Asia: a brief introduction to the key issues. Reg. Dev. Dialog. 20, 143–163.

Booth, D., Hanmer, L., & Lovell, E. (2000). Poverty and transport. Report for the World Bank, Overseas Development Institute.

Cebollada Frontera, À. (2006). Aproximación a los procesos de exclusión social a partir de la relación entre el territorio y la movilidad cotidiana. Documents d’anàlisi geogràfica, (48), 105-121.

Litman, T. (2021). Transportation Affordability: Evaluation and Improvement Strategies. Victoria Transport Policy Institute.

Lucas, K., Mattioli, G., Verlinghieri, E., & Guzman, A. (2016). Transport poverty and its adverse social consequences. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers – Transport, 169(6), 353–365.

Martens, K. (2017). Transport Justice: Designing Fair Transportation Systems. Routledge

Mejía Dorantes, L., Murauskaite-Bull, I. (2023). Revisiting transport poverty in Europe through a systematic review. Transportation Research Procedia, 72, 3861-3868. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trpro.2023.11.497.

Social Exclusion Unit (2003). Making the Connections: Final Report on Transport and Social Exclusion